***

A big thank you to our partner who is sponsoring this 4-part series and keeping the content free for you:

Develop better habits: Leaders at Spotify, Y Combinator, and Lightspeed organize their life with Sunsama — the daily planner for busy professionals. It helps you manage your tasks, meetings, and emails all in one place. Get the tool trusted by the world’s most successful performers.

If you click a link and make a purchase, I may earn a small commission (at no extra cost to you).

***

⚡️ Today’s level up ⚡️

I would rate my negotiation skills as “slightly above average.” It was good enough to get deals done, but not exceptional. To fill in the gaps, I always benefited from using frameworks. Today’s edition highlights one of four of the best negotiation frameworks used in business today. Let’s dive deep into the first one: Principled Negotiation.

Let’s go!

Read time: <9 minutes

If you missed last week, read it here.

Negotiating blindly leaves a lot of money on the table

Negotiation was not my strong suit.

Although I wasn’t completely inept at it, it certainly wasn’t my specialty. Throughout my career, I was good enough to always get what I wanted in each role I took on, and I was comfortable enough to negotiate deals on my own through working as an Enterprise AE.

However, things drastically changed when I leveled up to becoming a Strategic Account Director focused on positioning and winning transformation deals with Fortune 500 brands.

Both the size of the companies and the deals I was pursuing ballooned. Relying solely on my past skill stack was not going to be enough. And as a systems thinker, I naturally gravitated towards implementing frameworks to guide my business decisions.

Negotiation was no different.

Here is the first of four of the best negotiation frameworks used in business today that will help you negotiate deals like a savvy Fortune 500 CEO.

(And be sure to read all four parts, as I will share a free gift you can use at the end of the series.)

Negotiation Framework #1: Principled Negotiation

This framework, from the business classic book Getting to Yes by Roger Fisher and William Ury, focuses on better negotiation through resolving conflicts.

Born from The Harvard Negotiation Project (more on that in the next edition), it remains one of the top negotiation and business resolution frameworks cited by prominent CEOs and entrepreneurs.

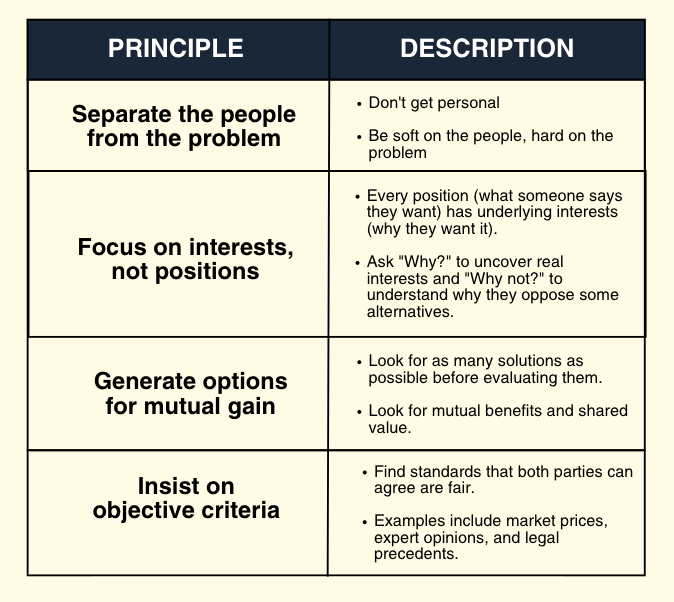

It comprises four key principles:

1. Separate the people from the problem.

Every negotiator is a human being, and each person brings their own perspective, emotions, and ego to the negotiating table (hence why I promote ”Human First, Professional Second.”)

People can easily feel frustrated, angry, or threatened or infer offense when none was meant. This can often derail negotiations even when agreement is possible. This is why Fisher and Ury say you need to “separate the people from the problem.”

Here are some helpful ways to do so:

→ See things from the other side’s point of view

What do they want to happen? What are they afraid might happen instead?

Communication becomes easier when you make it feel like both sides are on the same team versus operating as competitors.

Perhaps you’ve found yourself in a tough situation where you’ve inherited an account that puts people above the problem, leaving both sides pointing fingers at each other.

Elevate above it and get to the real problem. That starts with understanding their point of view.

Here’s a simple example to illustrate the point:

Let’s say someone hires a plumber to fix their kitchen sink. A week later, the sink breaks again. Frustration ensues. They could call the plumber and get angry, but if they blame the plumber directly, the plumber might get angry and refuse to help. But the kitchen sink is the problem, not the plumber.

Don’t confuse the person with the problem.

→ Defuse negative emotions.

Negative emotions make negotiation especially challenging. If any participant is angry, upset, or scared, it makes communication harder than it needs to be.

When you face this, let’s say, with an unhappy customer, acknowledge that they are legitimate – which all starts by understanding where they are coming from.

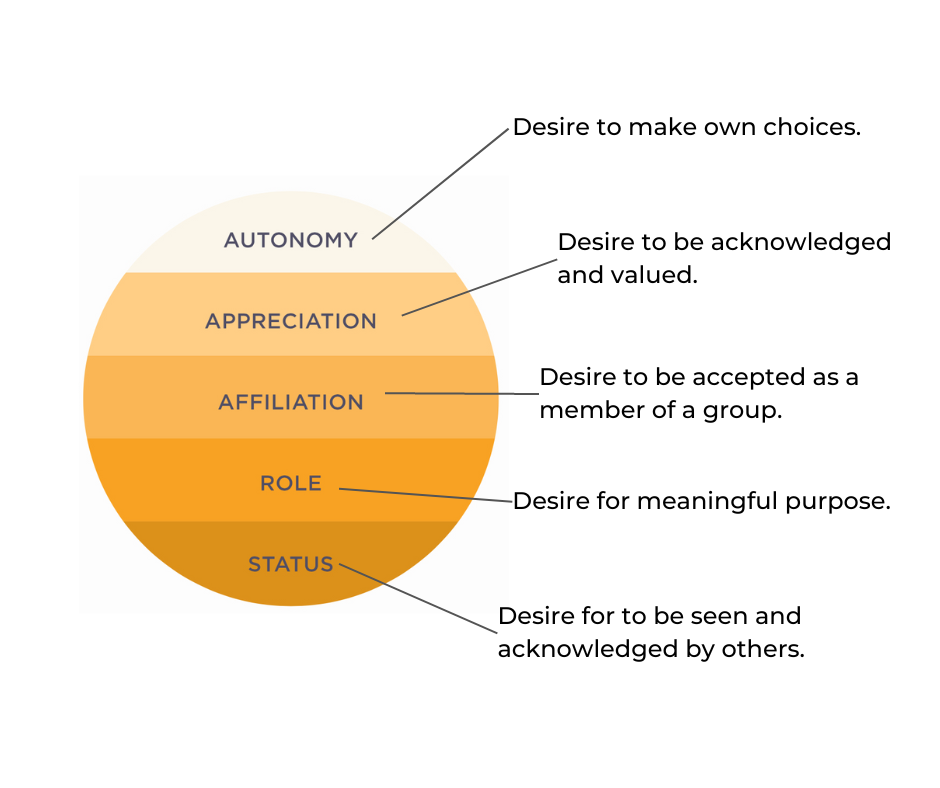

In most cases, emotions within negotiations are driven by one of five “core concerns.”

When these core concerns feel threatened, negative emotions follow. If we acknowledge and deal with emotions, we can limit unnecessary negative reactions and help our team and our clients stay focused on the problem, not the people…opening the conversations for better negotiation.

→ Use open communication.

Good negotiations require active listening.

One of the areas I fell short on early in my sales career was listening to respond versus listening to understand. Once I graduated to working on strategic accounts and recruiting other senior executives specializing in negotiating complex deals, I learned what it meant to be a better active listener.

Instead of listening to what I wanted to hear to get the deal done, I got better at putting myself in the other side’s shoes – realizing fully how a deal needed to be structured to meet their strategic initiatives as individuals and as an organization.

For example, you might say, “You have a strong case. Do I have it correct that you want…”

By helping your clients feel heard, they in turn are more inclined to actively listen to your side’s point of view.

2. Focus on interests, not positions.

Two people start arguing in a library.

The first person insists on opening the window. The other person wants the window closed. They try to compromise, but they end up arguing.

They fight over whether the window should be half open, or one-quarter open, etc.

A librarian enters. She asks each person why the window should be open or closed.

The first person explains they want to let in fresh air. The second person explains they don’t want to let in a draft.

Then, the librarian walks to the adjoining room and opens a window there. This lets in fresh air without the draft.

How did she arrive at this idea?

Instead of trying to do what each person proposed, she focused on what they actually wanted. This is a simple example of “focus on interests, not positions.”

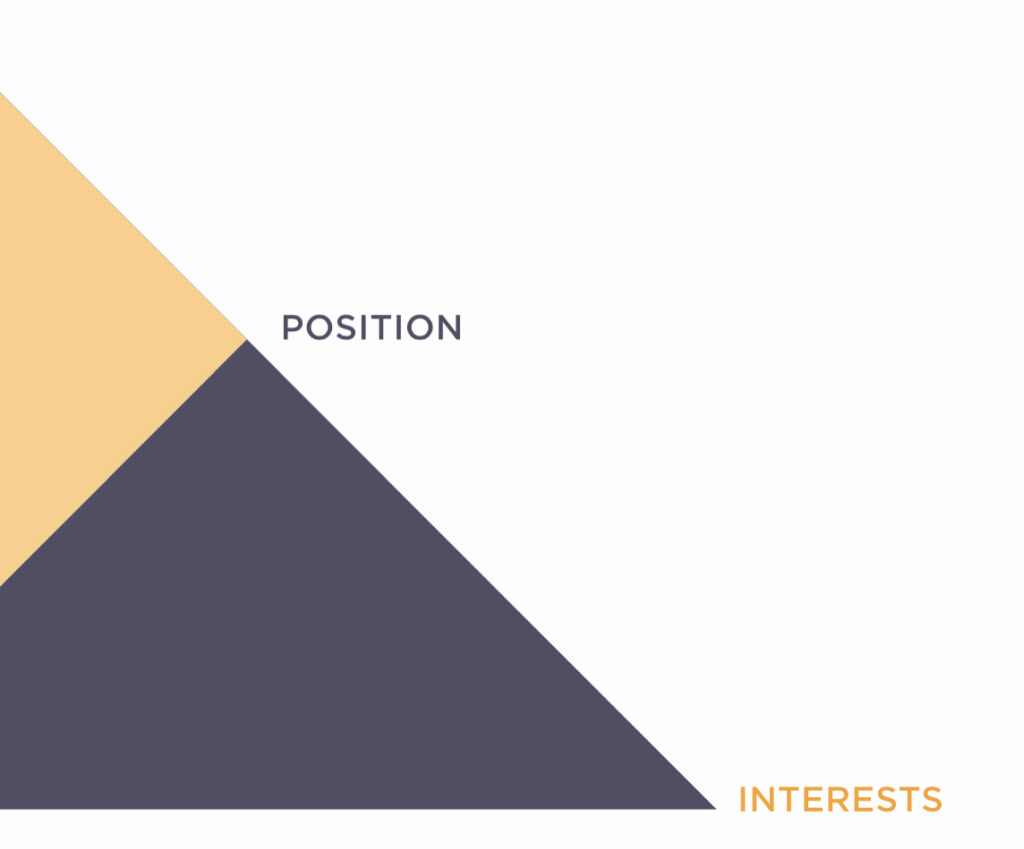

A position is a specific demand (like opening the window). An interest is a motivating factor behind a demand (like the desire for fresh air).

Our interests come from our needs, fears, hopes, and desires. And our positions are ways we think we can satisfy our interests.

But interests and positions do not have a one-to-one relationship. There are several ways to satisfy each interest. And some of these ways might also satisfy the other side’s interests.

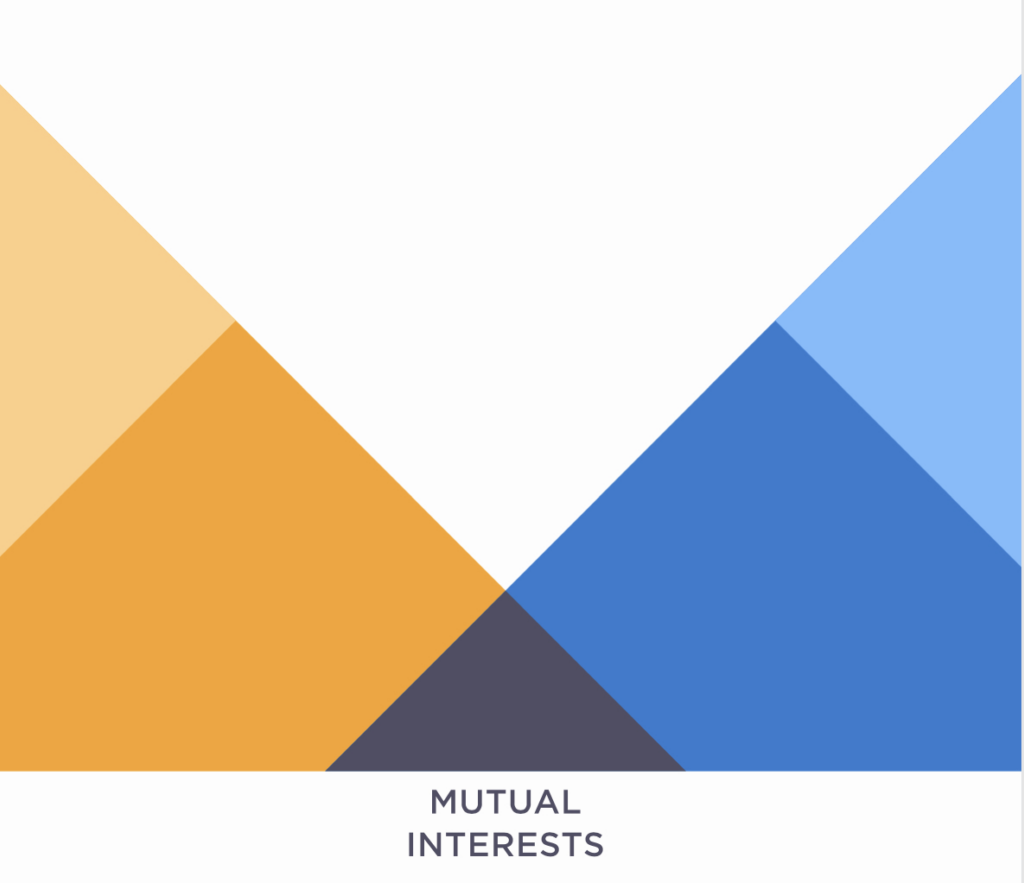

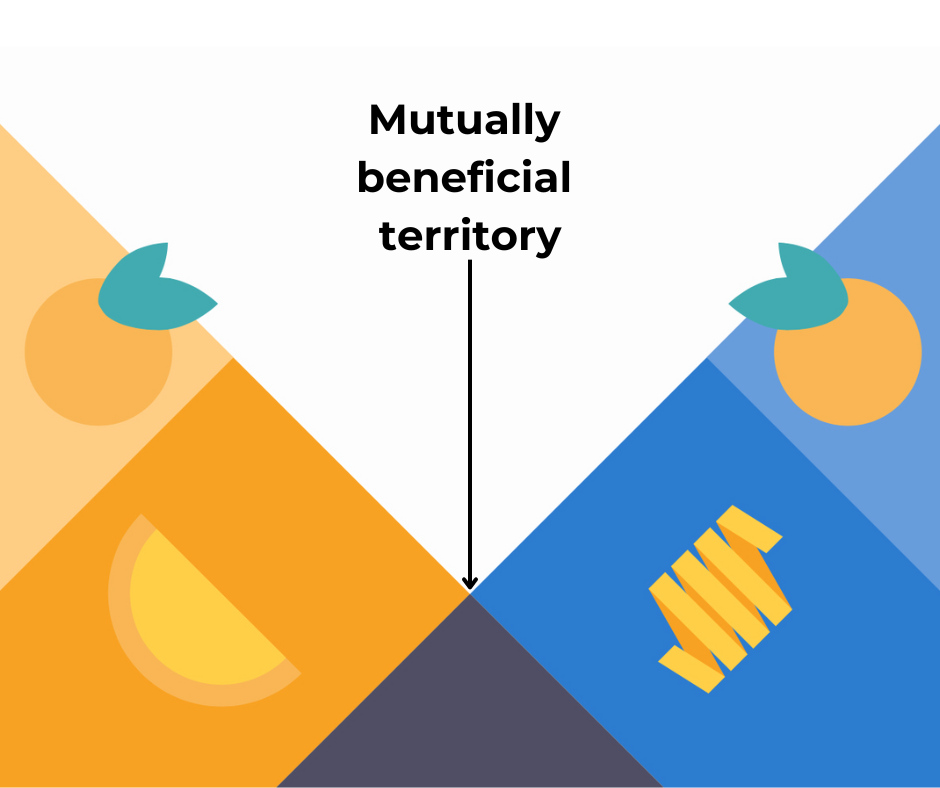

To be a successful negotiator, you’ll want to focus your effort where both side’s interests intersect.

For example, I pursued business with a large healthcare company with several business units (each business unit was the size of a Fortune 500 company by itself), and I had to orchestrate a tricky negotiation on both sides.

Our company cared about deploying a usage-based consumption model that consumed more and more credits as they matured on the platform. As a net new customer, they cared about an agreement that allowed them to lock in lower consumption rates now based on their size and projected use.

Instead of fighting over projected use and rates, we focused the majority of our efforts on mutual interest – a multi-year agreement. As a starting point, we eventually got to a level playing field where two years was the proper time to meet both our needs.

That led to ending an 18-month sales cycle and starting a multi-million dollar effort on one business unit with tons of room for expansion based on performance. Everyone felt comfortable and left the negotiating table satisfied.

The key is asking the (sometimes hard) questions to find the real interest behind their position. That puts you in a spot to find overlap between both sides’ interests and focus your negotiations around those.

3. Generate options for mutual gain.

Most people negotiate with a specific outcome in mind.

For instance, they may think of a price and then demand that it be met. Or they demand a particular concession from the other side and refuse to accept any agreement without it.

When success is measured this way, only one party can win. The negotiation becomes a zero-sum game. For one party to win, the other has to lose. Nobody wants to lose, so most negotiations fall apart in this type of approach.

No one wins.

However, if you find ways for the outcome to benefit both parties, you can give a negotiation a better chance of success. As Fisher and Ury describe it: “Expand the pie before dividing it.” In other words, you’ll need to reframe the negotiation to include new factors.

If you create more options, you’ll have more opportunities to reach agreement.

Let’s use a simple example to illustrate the point.

Imagine your landlord wants to raise your rent. You object to the rent increase, but your landlord won’t budge. You can continue to argue about the increase, but if you do, there’s a good chance you won’t be happy with the outcome (needing to find a new place to live).

How can you turn this into a negotiation that benefits both parties?

Consider your other interests and bring them to the table. Maybe you would be willing to pay higher rent if the landlord upgraded your appliances. Propose these ideas to the landlord, and you have a better shot at reaching a mutual agreement.

In your deals, you’ll need to brainstorm if you want to invent mutually beneficial options.

Brainstorming requires a safe environment to think and discuss ideas with others. Usually, you’ll want to brainstorm in private with people you trust (like your Mobilizer), apart from the other sides of the negotiation (i.e. Legal and Procurement).

Before you brainstorm, choose someone to facilitate the discussion. The facilitator should make sure no ideas are criticized. This way, people will feel comfortable contributing great ideas. Once you’re finished brainstorming, choose the ideas that seem the most promising.

Find options for mutual gain by assessing each side’s interests.

Once you’ve generated a list of possible options, you must decide which would be mutually beneficial. You want to make it easy for the other side to say yes to an agreement. But you also want to satisfy your own interests.

First, consider if you share any interests with the other side. Shared interests may reveal new opportunities for mutual benefit. For instance, if you and your landlord want stability, you might negotiate a longer lease.

But more often, opportunities for mutual gain come from differing interests rather than shared ones.

For example, Fisher and Ury tell the story of two children fighting over an orange. Only one child wanted to eat the orange. While the other wanted to peel the skin and use it to bake a pie. While their interests were different, they were entirely compatible.

To find options that are mutually beneficial, remember to identify each side’s specific interests. What’s important to you may not be important to the person on the other side and vice versa. In these cases, you can each offer something that appeals to the other side’s interest, and reach an agreement.

4. Insist on objective criteria.

Too often, negotiations get stuck.

You and the other side simply can’t reach an agreement. They think your price is unfairly high. And you think their ask is unfairly low. Both sides try to hold out until the other side gives in.

In some cases, the negotiation will fall apart. In other cases, someone will win, but both sides waste time and resources trying to outlast each other. And afterward, the two sides may resent each other…not producing the foundation for a strong strategic partnership.

How do you resolve these types of conflicts?

Ury and Fisher recommend using “objective criteria.”

Objective criteria is independent of either side’s desires.

Criteria are standards for evaluating something. They can be objective or subjective.

Subjective criteria are based on someone’s own perspective. For instance, in a salary negotiation for a new role, you might think the proposed salary is insultingly low for someone with your experience.

But your employer might think it’s fair because the business is struggling. These positions are based entirely on each side’s unique perspective. And the negotiation will only move forward if one side gives in.

However, objective criteria are totally independent of either side’s opinions and desires.

By focusing on facts and fairness, you can resolve disputes and reach an agreement that both sides will think is reasonable. Here’s how:

→ Use accepted standards to establish fairness.

For instance, if you are negotiating a new salary or comp plan for an elevated role in your organization, you might use RepVue to use objective data that collects salary and comp data from the market.

When you consult accepted standards, you can support your position with facts, which gives it more credibility.

→ Develop fair procedures to resolve disputes.

The second way to apply objective criteria is to change the negotiation process.

A fair process can force all sides to think about what is fair, instead of what is best for themselves.

For example, consider two kids arguing over a birthday cake. They both want to get the biggest slice. You can have one child cut the slices, and the other child chooses their slice first. This approach makes it feel more like a fun game, and neither child (should) complain about unfairness.

It’s important to note that fair procedures won’t always result in equal outcomes (i.e. the same-sized slice of birthday cake), but they ensure that each side has equal opportunity (i.e. cutting or choosing the first slice).

→ Work with the other side to agree on a shared objective criteria.

Objective criteria are most effective when both sides agree to use them.

For example, let’s say you’re buying a house. Before you propose a specific price, discuss what objective standards you can use to decide on a fair price. Frame it as a shared goal to find a good solution.

You could say, “We both want this sale to happen. How can we pick a fair price together?”

You might suggest looking at the average prices of other houses in the neighborhood. They might have their own suggestions, like having an independent party appraise the home. Discuss these ideas and decide which ones make the most sense for both of you.

Later, you can consult the criteria you agreed on. If the other side proposes a very high price, you can simply ask, “What’s you’re thinking behind this?”

They might say the house next door sold for a similar amount. Then you could say, “That’s reasonable, but let’s also look at the average prices across the neighborhood like we agreed.”

Insist on using the objective criteria that you both agreed to in advance. Then, you’ll be more likely to reach a place you both agree is fair.

Summary (TL; DR)

Negotiation will not only serve you well in business, but in life.

I want to give proper space for this incredibly important skill, and as such, I am dedicating one newsletter for four weeks straight to the four most powerful negotiation frameworks used in business today.

Today’s edition focused on The Principled Negotiation Framework (from Getting to Yes by Fisher and Uri). It’s a great framework to use for conflict resolution and comprises of four key principles:

Next week, I’ll dive deeply into The Seven Elements Framework. See you then!

Here’s how I can help you right now:

1 | Unlock the 7 Figure Seller OS

Learn how to use design and systems thinking to become a 7 figure seller. There are 3 options to allow you to customize your learning journey.

2 | Download The 7 Figure Open Letter

Get the creative strategic selling strategy that landed a $5.9M deal with a top 4 major global airline. Bonus inside!

3 | Book a 1:1 coaching session right now

You can book a 60-minute coaching session with me (although the Pro above option provides access to 1:1 coaching with me at a 70% discount. Note, just a handful of available coaching slots remain for 2023).